Harness the Possibilities of Macrophage Immunomodulation

The macrophage is a remarkably adaptable and heterogeneous cell type that is central to both health and disease. Macrophage modulation strategies are leading to novel therapeutic approaches in cancer, infection, COVID-19, and more.1–4

Macrophages are a heterogeneous class of leukocytes with a critical role in health and homeostasis2

Though widely recognized as phagocytes that clear debris and pathogens, macrophages constitute a complex homeostatic system distributed throughout the body.5,6

Macrophages contribute to a broad range of important functions, including:

Macrophages are extraordinarily heterogeneous with individual function determined by phenotype expression1,8

The framework for understanding and classifying macrophage phenotypes has evolved to account for their plasticity and context-dependent nature.7

Traditionally, macrophage phenotype has been categorized into 2 major subtypes—the classically activated, inflammatory (M1) phenotype and the alternatively activated, anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotype. However, it’s now understood that macrophages exist along a phenotypic spectrum, demonstrating remarkable fluidity in response to various extrinsic and intrinsic factors.5,8

Explore the different types of stimuli that influence macrophage phenotype and function

Macrophages are present in all tissues. Resident macrophages exist in distinct subpopulations based on anatomical location, including1,6,8,10:

- Brain

Microglia - Lung

Alveolar macrophages - Spleen

Red pulp macrophages - Liver

Kupffer cells - Blood and bone marrow

Resident and infiltrating monocytes - Bone

Osteal macrophages

Resident macrophages become activated when they detect early danger signals, such as2:

- Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) released from invading pathogens

- Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released from damaged or dead cells

- Activation of tissue-resident memory T cells by antigens

As infection or injury progresses, various disease-specific stimuli can induce polarization or re-polarization of recruited and resident macrophage populations. For example, in cancer, the phenotype of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) can be readily modified by the tumor microenvironment at different stages of disease progression.2

Macrophages originate from 2 distinct lineages, which, in recent years, has been shown to correspond with their predominant function in the body.2

- Embryonically derived macrophages

Most tissue-resident macrophages arise during embryogenesis in the fetal yolk sac and do not have a monocytic progenitor. They are self-regenerating and primarily involved in tissue maintenance and remodeling2,5 - Adult-derived macrophages

After birth, bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells give rise to monocytes that replenish tissue-resident macrophage populations with high turnover, such as those in the gut. During infection or injury, monocyte-derived macrophages are also recruited to assist in host defense5

Phagocytosis by macrophages has essential immunomodulatory effects throughout the body, but also alters the metabolism and function of macrophages themselves.11,12

Macrophage adaptations after phagocytosis of inflammatory stimuli1,12:

- Shifting to glycolysis to meet the increased energy demands of host defense

- Producing antimicrobial agents, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), to help kill invasive pathogens

- Increasing expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines to stimulate adaptive immunity

Macrophage adaptations after phagocytosis of anti-inflammatory stimuli11,12:

- Upregulating glycolysis and increasing oxidative phosphorylation to reduce expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines

- Secreting immunomodulators, such as TGF-ß and IL-10, that inhibit pro-inflammatory mediators and further promote resolution of inflammation

Macrophages respond to changes in their environment and nutrient intake to maintain metabolic homeostasis. They regulate important metabolic functions in both health and disease.1,2

For instance, in pro-inflammatory conditions such as infection, macrophages promote peripheral insulin resistance and decrease nutrient storage. This allows macrophages and other activated immune cells to shift to glycolysis for a faster source of energy while defending against pathogens.1,2

In contrast, functions like tissue repair and epithelial healing require a sustained source of energy. This is supplied by oxidative glucose metabolism and fatty acid oxidation in macrophages.1,2

Cytokines are potent signaling proteins that mediate intracellular communication and host immune response. The local cytokine milieu influences macrophage function and induces polarization toward an anti- or pro-inflammatory phenotype.2,13

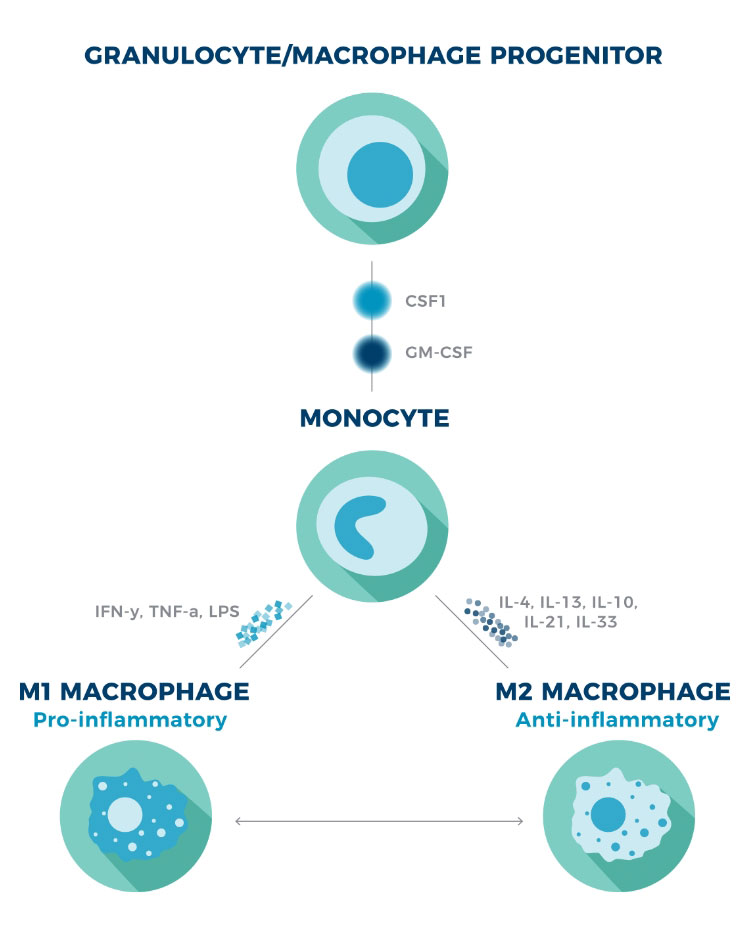

Traditional categorization of macrophage phenotype into M1/M2 was first introduced to be consistent with the classification of Th1/Th2 cells. Scientists now agree this nomenclature doesn’t sufficiently capture the plasticity and complexity of macrophages. However, it remains a useful framework when discussing cytokines’ typical influence on macrophage phenotype.14,15

Typically speaking, M1 macrophages are polarized by inflammatory Th1 cytokines, whereas M2 macrophages are induced by anti-inflammatory Th2 cytokines.2

Regardless of phenotype, cytokines also regulate the production and survival of macrophages. The cytokines CSF1 and GM-CSF are particularly important due to their critical role in the differentiation, activation, and survival of macrophages.16

Macrophage polarization1,2

CSF1=colony-stimulating factor 1; GM-CSF=granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; LPS=lipopolysaccharide.