Tissue-resident macrophages and recruited monocytes are critical defenders against invasive pathogens.1

Macrophage polarization during infection:

Initial activation

In the early stages of infection, macrophage activation occurs upon detection of a microbe expressing one or more danger signals, termed pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs).2

Inflammatory immune response

This induces macrophages to undergo profound physiological changes, releasing a variety of pro-inflammatory mediators to activate host immunity and promote pathogen killing.3,4

Resolution of inflammation

Once the infection is controlled, macrophages polarize toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype to modulate inflammation and repair tissue damage.4,5

However, macrophage polarization occurs along a dynamic continuum and can vary depending on the causative agent of infection and local environment2,3

Many pathogens have developed mechanisms to modulate macrophage function and evade immune detection1-3

These techniques induce macrophages to dampen inflammation, decrease antimicrobial activity, and inhibit phagocytosis. This creates a favorable environment for pathogen persistence and proliferation.1-3

As such, it is increasingly recognized that immunologic response is a key determinant of outcomes in infection. This may help explain the persistence of high mortality rates from infection despite major advances in antimicrobial agents.6,7

Strategies that reshape macrophage activity and synergize with antimicrobial agents represent a promising new approach to infectious disease1,6,7

Interventions that target macrophage polarization rather than the pathogen itself have shown promise as a new therapeutic strategy in infection.1-3

One approach to enhance macrophage activity is by administering cytokines that can have anti- or pro-inflammatory effects. The cytokine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is a promising candidate because of its ability to stimulate the growth and survival of multiple immune cell types, including mature tissue macrophages and monocyte progenitors.4

Administration of exogeneous GM-CSF not only increases the number of macrophages, but also augments their antimicrobial activity.5

Numerous preclinical studies have confirmed the beneficial effects of GM-CSF administration on macrophage function, including4,5:

- Boosted chemotactic, anti-fungal, and anti-parasitic activity

- Increased phagocytosis of microbes

- Reversal of corticosteroid-induced immunosuppression

- Enhanced antigen-presenting capacity

GM-CSF has been shown to enhance macrophage microbicidal activity in vitro and protect against lethal infection in vivo against5:

- Candida albicans

- Aspergillus fumigatus

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Mycobacterium avium complex

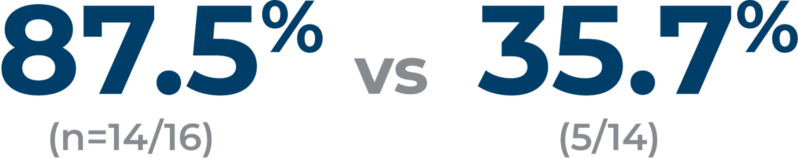

Based on these preclinical results, GM-CSF is under investigation as a novel therapeutic approach for difficult-to-treat infections in various patient populations6